In this instalment we talk to architect Jade Kake about design from a Māori perspective, and provide some tips for positive collaborations between Māori and non-Māori.

In GSM23, we featured BEST purple winning project; Rewi: Ata haerre, kia tere. A book celebrating the work of Māori architect Rewi Thompson. Following on from this, we reached out to author of the book, Jade Kake, architect and housing advocate. We asked Jade for her thoughts around design from a Māori perspective. Whilst her thoughts centre around the built-form, much of this can easily be applied to visual communication. Here’s what Jade had to offer…

In GSM23, we featured BEST purple winning project; Rewi: Ata haerre, kia tere. A book celebrating the work of Māori architect Rewi Thompson. Following on from this, we reached out to author of the book, Jade Kake, architect and housing advocate. We asked Jade for her thoughts around design from a Māori perspective. Whilst her thoughts centre around the built-form, much of this can easily be applied to visual communication. Here’s what Jade had to offer…

Kia ora koutou. Ko Jade Kake tōku ingoa. He kaihoahoa whare ahau. Ko Ngāpuhi rātou ko Te Whakatōhea ko Ngāti Whakaueōku iwi. My name is Jade Kake, I’m an architect and I whakapapa to the Ngāpuhi, Te Whakatōhea and Ngāti Whakaue tribes. For this article, I’ve sketched out a few core concepts that, in my view, characterise ‘Māori design’. Meaning; design by Māori designers, architects and artists. Some iwi or hapū may reject this framing in favour of mana whenua-led design, or [iwi/ hapū name here]-design. This is perfectly valid. I use ‘Māori design’ here for clarity and broader applicability. Remember, if you are a non-Māori designer, you are able to participate in Māori design as a collaborator, but you are unable to lead.

Kia ora koutou. Ko Jade Kake tōku ingoa. He kaihoahoa whare ahau. Ko Ngāpuhi rātou ko Te Whakatōhea ko Ngāti Whakaueōku iwi. My name is Jade Kake, I’m an architect and I whakapapa to the Ngāpuhi, Te Whakatōhea and Ngāti Whakaue tribes. For this article, I’ve sketched out a few core concepts that, in my view, characterise ‘Māori design’. Meaning; design by Māori designers, architects and artists. Some iwi or hapū may reject this framing in favour of mana whenua-led design, or [iwi/ hapū name here]-design. This is perfectly valid. I use ‘Māori design’ here for clarity and broader applicability. Remember, if you are a non-Māori designer, you are able to participate in Māori design as a collaborator, but you are unable to lead.

Ngā Rawa (Materials)

The basic idea is that raw materials that are grown locally, processed locally, and then constructed locally, using local skills and labour, have greater cultural integrity and resonance than highly processed materials with a high carbon footprint. In a globalised world, with a largely off-the-shelf construction industry, this can be difficult to achieve. Our technological development has essentially been stifled by colonisation, with damaging and harmful statutes such as the Tohunga Suppression Act 1907 and the Raupo Houses Ordinance 1842 essentially making Māori building technology illegal. This resulted in a loss of critical skills and preventing further technological development. And this led me to become increasingly interested in contemporary Dutch thatch technology as a way of filling in some of the missing gaps and support the development of contemporary Māori raupō thatch technology.

Ngā Tauira (Motif)

Patterns and motifs hold deep cultural meaning. They can significantly alter the look and feel of buildings and landscape to support a sense of place and cultural associations. Traditional motifs are the domain of highly trained traditional arts practitioners. They may also be skilled in its contemporary application, or be able to collaborate with those who are doing this, by supporting them to translate this meaning into architectural materials and form. Cultural expression should not be limited to patterns. However, this can be an effective and highly visible form of expression, particularly within the public realm.

Patterns and motifs hold deep cultural meaning. They can significantly alter the look and feel of buildings and landscape to support a sense of place and cultural associations. Traditional motifs are the domain of highly trained traditional arts practitioners. They may also be skilled in its contemporary application, or be able to collaborate with those who are doing this, by supporting them to translate this meaning into architectural materials and form. Cultural expression should not be limited to patterns. However, this can be an effective and highly visible form of expression, particularly within the public realm.

Whakatakoto (Layout)

The arrangement of spaces is critical to the use of space in ways that are culturally desirable and in the enactment of cultural protocols. The foremost consideration is the separation of tapu (restricted) and noa (unrestricted) functions. Within our kāinga or traditional villages, whare (houses or other buildings) were clustered around a central ātea or courtyard. The separation of function is related to the separation of tapu and noa noted above, as well as practical reasons relating to construction technology and available resources. Kawa and tikanga are related concepts. Kawa is fixed, stative and tikanga is unfixed and can be changed by collective agreement.

The arrangement of spaces is critical to the use of space in ways that are culturally desirable and in the enactment of cultural protocols. The foremost consideration is the separation of tapu (restricted) and noa (unrestricted) functions. Within our kāinga or traditional villages, whare (houses or other buildings) were clustered around a central ātea or courtyard. The separation of function is related to the separation of tapu and noa noted above, as well as practical reasons relating to construction technology and available resources. Kawa and tikanga are related concepts. Kawa is fixed, stative and tikanga is unfixed and can be changed by collective agreement.

Kaumātua (ideally a representative group, rather than an individual) are best placed to debate and achieve agreement on changes to tikanga. This is particularly important in its enactment in institutional spaces where tikanga cannot always be consistently maintained by the relevant hapū (subtribe) or mana whenua group (those with inherited rights and responsibilities within a defined territory).

Āhuatanga (Form)

The form of the building can denote specific cultural associations and relationships. In Aotearoa, our historic forms include the gabled meeting house, with the mahua (porch) at one end and the centrally situated posts. In our architectural history, there have been many creative reinterpretations of traditional form, including the cruciform house Te Miringa Te Kakara, the circular Hīona, and the ten-storey multilayered Tapu te Ranga Marae.

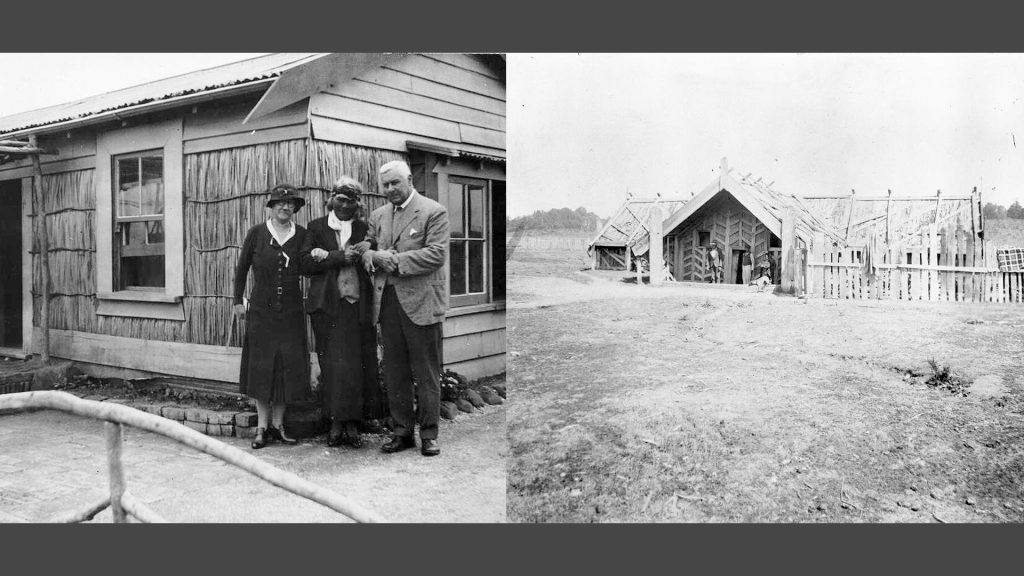

Te Puea Herangi’s whare (date and photographer unknown). This Land Development Scheme house shows the use of traditional Ngā Rawa (materials) in the exterior thatched walls. A way of building that uses sustainable, local materials. (above left)

Te Puea Herangi’s whare (date and photographer unknown). This Land Development Scheme house shows the use of traditional Ngā Rawa (materials) in the exterior thatched walls. A way of building that uses sustainable, local materials. (above left)

This meeting house at Tiroa, Te Miringa Te Kakara, with its gabled roof and mahua (porch), is an excellent example of traditional Āhuatnaga or form (above right).

Ngā Tikanga (Protocols)

In addition to the design or arrangement of spaces to accommodate cultural protocols, there are a number of protocols specifically relating to the construction of a whare. Most of these protocols take the form of cultural ceremonies led by skilled kaikarakia (those with knowledge and expertise in traditional/non-Christian prayers or affirmations). These include protocols followed before extracting the raw material (felling a tree or harvesting fibres), for laying a mauri stone under the first post, for the placement of tapu (restriction) at the beginning of construction, and the removal of tapu at its conclusion. There may also be specific protocols followed at the commencement of earthworks.

In addition to the design or arrangement of spaces to accommodate cultural protocols, there are a number of protocols specifically relating to the construction of a whare. Most of these protocols take the form of cultural ceremonies led by skilled kaikarakia (those with knowledge and expertise in traditional/non-Christian prayers or affirmations). These include protocols followed before extracting the raw material (felling a tree or harvesting fibres), for laying a mauri stone under the first post, for the placement of tapu (restriction) at the beginning of construction, and the removal of tapu at its conclusion. There may also be specific protocols followed at the commencement of earthworks.

Advice for non-Māori designers

If you are a non-Māori architect or designer working in Aotearoa New Zealand, I encourage you to start by learning about Te Tiriti o Waitangi (The Treaty of Waitangi), our founding agreement and the basis for our constitutional arrangements. The Treaty is important because it enables all of us—Māori and non-Māori, tangata whenua and tangata tiriti—to co-exist in Aotearoa New Zealand and to jointly govern our nation in ways that are culturally meaningful to us.

A deeper understanding of the history of the whenua (land) and our separate but interconnected shared roots, enable us to develop design responses that are genuinely grounded in the unique culture, history and identity of our place in the world. There are some fantastic Treaty educators and Treaty education resources available—Network Waitangi is a great place to start. For non-Pākehā tauiwi (non-Māori), there are various groups that are active in this space, including Asians Supporting Tino Rangatiratanga.

A few key points to remember:

- Process is equally, or perhaps more, important than the outcome. A good quality process and respectful, enduring relationships are key to a successful outcome.

- Consider your own positionality. Your involvement in projects may be perfectly valid, but critically considering your own positionality will help you determine your role. As a conceptual design leader, or as a supporting collaborator. Whilst you may not be qualified to lead the selection and interpretation of Māori cultural concepts through design, you are qualified to support Māori architects, designers, culture knowledge holders, artists and mahi toi practitioners through collaboration.

- Your own culture and whakapapa (genealogy) is the gateway to authentically understanding and connecting to Māori culture—embrace it!

- Making mistakes is okay! People will respect your efforts if you approach your work with openness and curiosity and leave your ego at the door.

TE IWITAHI

Completed in 2024, Team Avery Architects designed the award-winning 8,330 square metre Te Iwitahi Civic Centre in Whangārei. Matakohe Architecture + Urbanism collaborated on the project as the hapū-appointed designers. We were tasked with facilitating the articulation of hapū cultural values, narratives and aspirations, and the appropriate incorporation of tikanga and mātauranga Māori within the project.

Completed in 2024, Team Avery Architects designed the award-winning 8,330 square metre Te Iwitahi Civic Centre in Whangārei. Matakohe Architecture + Urbanism collaborated on the project as the hapū-appointed designers. We were tasked with facilitating the articulation of hapū cultural values, narratives and aspirations, and the appropriate incorporation of tikanga and mātauranga Māori within the project.

The motif (left), installed under the cantilevered first floor, is visible in the photo of the finished entrance facade (top).

The motif (left), installed under the cantilevered first floor, is visible in the photo of the finished entrance facade (top).

GSM would like to thank Jade Kake, Matakohe Architecture, for providing her thoughts to us for Rākau Kōrero.